Glen S. Fukushima, a third-generation American of Japanese ancestry from California, attended college at Deep Springs and Stanford. He did his graduate studies at Harvard and was an exchange student at Keio University, as well as a Fulbright Fellow at Japan’s most prestigious institution of higher learning, the University of Tokyo.

One of the most prolific subject matter experts on Japan, Mr. Fukushima has been engaged in U.S.-Japan relations since the 1970s. He has served in a variety of roles, one of the most notable being Deputy Assistant U.S. Trade Representative for Japan and China at the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative (USTR). He was also elected twice to serve as President of the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan (ACCJ). Since 2022, Mr. Fukushima was tapped by President Joe Biden to serve as Vice Chairman of the Securities Investor Protection Corporation (SIPC).

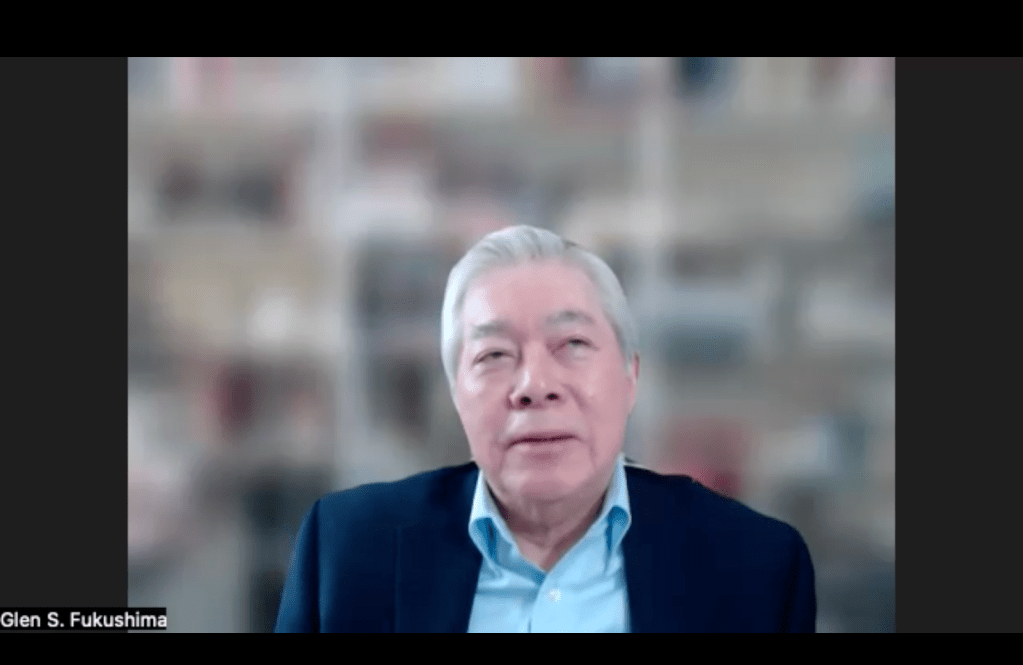

The Japan Lens sat down with Mr. Fukushima on Dec. 17, 2024 to hear his views on a range of issues in U.S.-Japan relations.

– – –

(Kafatos): Let’s start with the Japanese economy. Some say Japan’s shrinking population and so-called uncompetitive nature of its economy all but ensure its decline. Others disagree, such as Mireya Solis, who say Japan is actually pivoting towards smarter ways of competing in the global economy. How do you gauge the health of Japan’s economic competitiveness in the next decade?

(Fukushima): That depends on your definition of competitiveness and success because, on a macro level, there’s no question about it: with its declining population – compared to China, India, and Indonesia – Japan’s share of global GDP is declining.

At the same time, on a micro level, Japan is still one of the most stable and livable countries in the world. They have more Michelin 3-star restaurants in Tokyo than any other city in the world, the trains run exactly on time, it’s clean and safe. Also, individuals and companies can do very well in Japan. There are so many cases of individuals and corporations succeeding in Japan so, when assessing Japan’s economy, I think you have to look at both the micro and the macro.

(Kafatos): Much is made of Japan’s large debt ratio. Do you find that to be concerning as the population declines?

(Fukushima): The ratio of debt to GDP is a huge issue. But, unlike other countries, most of the debt is domestically held. There isn’t much fear the economy is going to crater and need to be bailed out, compared to other countries whose economies depend much more on external factors.

But certainly the burden is increasing on younger members of society to provide for the medical insurance, social welfare, and pension payments of the elderly. Japan is trying to deal with this by allowing a limited amount of immigration, or some would say “imported labor” because immigration is still a sensitive issue for some. There is also more automation because Japan is so advanced in robotics, and initiatives to tap into the female population and workers over 65. Japan is trying to cope with its demographic challenges, with varying degrees of success.

(Kafatos): Then there’s the challenge of being placed between the U.S., its largest defense partner, and China, its largest trading partner.

(Fukushima): That’s an issue of constant interest and concern in Japan. In terms of the political and security relationship, the U.S. is by far the most important country. But in terms of economics, since about 2010, China has been Japan’s largest trading partner.

“From Japan’s perspective, the ideal situation is to have a certain amount of tension between the U.S. and China so as to make Japan valuable to both. But not too much tension.”

Glen S. Fukushima

Investment has seen ups and downs but trade between Japan and China is increasing. Actually, about 15 years ago at a Council on Foreign Relations meeting, I predicted Japan will face this issue of the growing economic dependence on China, but continuing security and political dependence on the United States. Many of the Americans in attendance pooh-poohed this, failing to understand what I was talking about. But I think the trends were pretty clear, and it’s an ongoing issue.

Many people say the nightmare scenario for Japan is one where the U.S. and China become too friendly with each other, forming a G2 and marginalizing Japan. On the other hand, they don’t want tensions between the U.S. and China to increase too much because conflict will mean it has to choose between one or the other. From Japan’s perspective, the ideal situation is to have a certain amount of tension between the U.S. and China so as to make Japan valuable to both. But not too much tension.

(Kafatos): The incoming Trump administration is expected to issue tariffs against many countries, including Japan. There is also the issue of other protectionist actions, as seen in Nippon Steel’s failed bid to acquire U.S. Steel. What advice do you have for companies on both sides of the Pacific as they try to navigate this new age of American protectionism?

(Fukushima): The basics are the same as before, which is you have flexible and you have to really know what’s going on. Traditionally, businesspeople are trained to look at economic factors such as return on investment and the ability to raise money.

But with rising protectionism, the non-economic factors are become increasingly important to follow. Take the U.S. Steel matter. From a business point of view, when that proposed acquisition was announced in December of 2023, the initial reaction among U.S. business analysts was, “This is a great deal!” It’s good for auto producers, good for shareholders, for everyone. But later, key members of Congress came out in opposition. And then Bob Lighthizer, former USTR under Trump, came out in opposition. Then Trump, and eventually Joe Biden, came out in opposition as well.

(Re: the failed bid to acquire U.S. Steel)

Glen S. Fukushima

“Economically, it appeared to be a good deal. But Nippon Steel probably didn’t consider all the non-economic factors sufficiently.”

Economically, it appeared to be a good deal. But Nippon Steel probably didn’t consider all the non-economic factors sufficiently. It was a presidential election year, with Biden claiming to be the most pro-union president in U.S. history. He picketed with the United Auto Workers (UAW) during their strike. And Trump has a very strong attachment to steel because it plays a big role in his Make America Great Again agenda. Also, Pennsylvania was such a big battleground state. It will be increasingly important for companies to focus on the political environment and how that will affect their ability to do business.

In 2015 and in 2017, I was invited by the Kyoto University Graduate School of Management to teach a course on government/business relations. I relied on my experience at USTR and also 22 years working in business in Japan and Asia, and I used a lot of cases from Harvard Business School and MIT on the relation between government and business.

I concluded it is hard to avoid the impact of government, especially in advanced technology fields like telecommunications, IT, and semiconductors, but also in infrastructure and transportation. That’s increasingly the case.

(Kafatos): Around 2021, then-Prime Minister Kishida introduced his “new capitalism” concept as a counter to American capitalism which, in his view, produces some winners but also many losers. His form of capitalism – and more broadly Japanese capitalism – seems to place less emphasis on shareholders and more on stakeholders. How do you assess Japanese-style capitalism versus the American variety? Could it take root in America, or vice versa?

(Fukushima): From 1982 to ‘83 I was on a Fulbright Fellowship at the University of Tokyo. My research topic was antitrust law and policy in Japan. I was trying to compare it to American antitrust law and policy. One of the major differences, among many, is that antitrust operates in a different environment in the U.S. and in Japan, precisely because of the different forms of capitalism.

Prime Minister Kishida introduced his concept before the LDP presidential election in 2021. Initially, people were intrigued by it, but he kept changing what he meant by the term and, after a while, it kind of sputtered out.

To give it some historical perspective, at the end of the Cold War the competition between capitalism and communism/socialism was seen to have withered away. Then many sociologists, and economists, and political scientists started talking about the three forms of capitalism. There was the Anglo-American form, of the U.S. and UK; the German or Rhine form of Europe; and the Asian form of capitalism, which Japan represented. Experts like the sociologist Ronald Dore in Britain wrote very interesting comparisons about these three types of capitalism.

My conclusion is that, among the G7 countries, the U.S. and Japan are polar opposites. The UK is closer to the U.S., and Germany, France, Canada, and Italy are in between the U.S. and Japan, by a whole variety of measured indicators: income inequality; membership on corporate boards (to what extent they’re open to or have independent board members); compensation of senior executives; etc. There are about thirty indicators one can point to.

But there have been some significant changes in Japan. For example, the boards used to be completely internal, but now they have requirements – especially those companies listed on the stock exchanges – to have independent board members. There are also more women and non-Japanese on corporate boards. Sony was one of the early ones. I think Pete Peterson was the first non-Japanese board member of a major Japanese company. My wife, Sakie, was the first female board member at Sony. So there’s been change in the last 20-30 years. But Kishida felt Japanese capitalism didn’t pay enough attention to climate change and the environment, and to disparities between urban and rural areas.

“Among many people in Japan, there’s a realization that the inequalities and disparities in wealth in the U.S. are largely due to American-style capitalism. And that these have had a really negative effect on American society.”

Glen S. Fukushima

Still, Japan pays more attention to these areas than the U.S. does. A while back I was asked by the Council on Foreign Relations to give a presentation comparing American and Japanese capitalism. There are things the U.S. can learn from Japan, but I think it would be difficult to change American capitalism significantly. In August of 2019 the U.S. Business Roundtable issued a statement saying something to the effect of, “Up until now we’ve been so focused on shareholders, but we realize we have to focus more on stakeholders, not only shareholders.” This was in response to public opinion polls indicating an increased criticism of capitalism and all the inequalities it has created, and also less opposition to socialism, particularly among young people.

It’s important to note, when young Americans said they were more receptive to socialism, they didn’t mean in the sense of the government owning the means of production, or some hard Soviet model of the government taking control of the economy. They’re talking more about democratic-socialist ideas, like those of Sen. Bernie Sanders. Now, among many people in Japan, there’s a realization that the inequalities and disparities in wealth in the U.S. are largely due to American-style capitalism. And that these have had a really negative effect on American society.

There is rhetoric in the U.S. now with some saying, “We have to reconsider these disparities, and the role of the corporation.” And some Americans advocate for reforming traditional American corporate governance. Milton Friedman wrote in his 1962 book Capitalism & Freedom, which I read in Econ 101 as an undergrad at Stanford in the 1970s, that the only purpose of a corporation is to maximize profits for shareholders. That’s a pretty extreme position that most people in Japan would reject.

That’s because in Japan the purpose of a corporation is primarily to provide jobs and economic welfare for society. That’s why Japan has labor laws and practices that make it extremely difficult to fire people, which has pros and cons. Suffice it to say, American and Japanese capitalism are quite different. There are rhetorical attempts in the U.S. to move towards the Japanese model, and Japan is moving slowly towards the American model. But the two are still very, very different.

“Milton Friedman wrote… the only purpose of a corporation is to maximize profits for shareholders. That’s a pretty extreme position that most people in Japan would reject.”

Glen S. Fukushima

You can see this in the disparity between the pay of CEOs versus that of the average worker. There are studies that compare a CEO’s pay either with entry-level pay or with the average pay of all workers in the company. American CEOs earn many times more than their Japanese counterparts do, sometimes five to six times as much, sometimes much much more. I was on the board of several Japanese companies, and one of them was one of the top three banks in Japan. The Japanese CEO was making under $1 million in total compensation per year. His counterpart in the U.S. was making $35 million. This clearly shows how the forms of capitalism differ greatly between the two countries.

That was one of Carlos Ghosn’s issues when he was CEO of Nissan. From the Japanese point of view, he was making so much money compared to his peers at Toyota and Honda. But he was looking at the CEOs of GM, Ford, and Volkswagen who were making so much more than he was. That’s just one element of this disparity and difference in capitalism between Japan and the U.S./Europe.

(Kafatos): Is Japan likely to adopt practices from U.S. corporate governance? Or vice versa?

(Fukushima): I think there are limits to what Japan will adopt from the U.S. model. I think Japan fundamentally values continuity, stability, and predictability. Unless there is some overriding reason for change, people are likely to follow precedent. The view is, “If it ain’t broke don’t fix it.”

In the U.S., if there’s some dissatisfaction with the status quo, there’s a tendency to throw everything out and try something new. The view is it’s better to take action even if it has bad results rather than not take action, whereas in Japan the view is it’s best to not make changes unless absolutely necessary.

When people in Japan see the huge income and wealth disparities in the U.S. and the social problems they create, I think they will be very wary of incorporating elements of American corporate governance.

– – –

Click here for Part 2 of the interview with Glen S. Fukushima.

Photo 1: Glen S. Fukushima during his interview with the Japan Lens on Dec. 17, 2024.

Photo 2: President Joe Biden greets Glen S. Fukushima in May 2022 (Pacific Citizen).

No artificial intelligence or machine translation programs were used in the creation of this post.

2 responses to “Interview with Glen S. Fukushima (Part 1): Differences between American and Japanese capitalism”

[…] to prioritize profits for a limited group of wealthy, non-local shareholders. In contrast, as discussed by Glen S. Fukushima in a recent interview, Japanese corporations tend to focus on the well-being of all stakeholders, i.e., anyone affected […]

LikeLike

[…] is a continuation of Part 1 of our interview with Glen S. Fukushima recorded on Dec. 17, 2024 (transcript […]

LikeLike