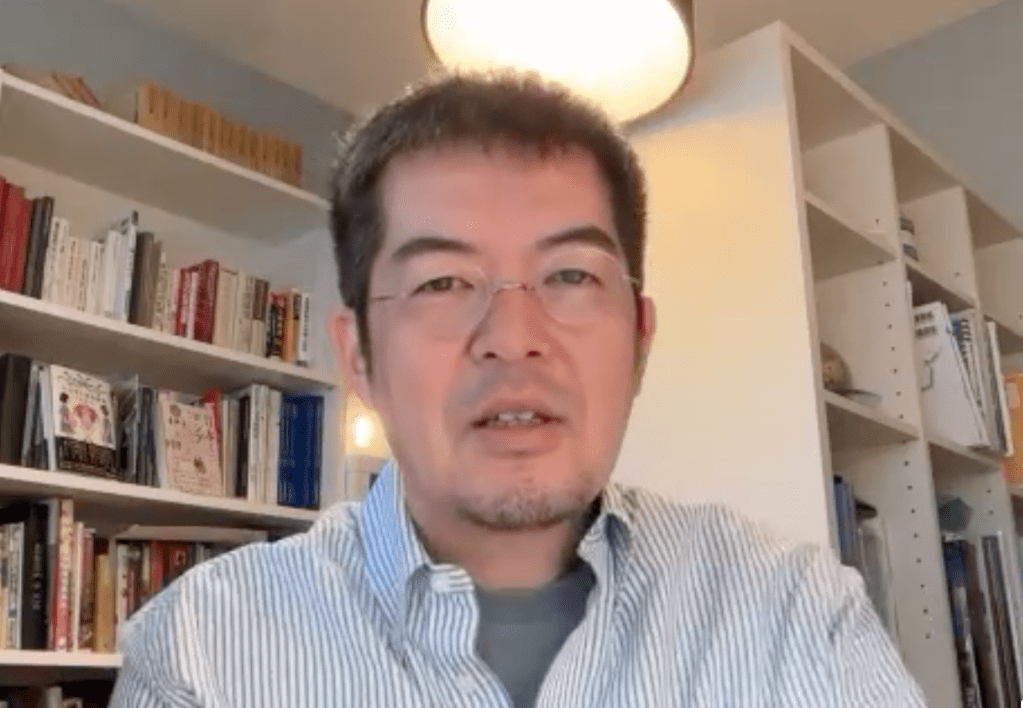

The Japan Lens recently recorded an interview with Yamaguchi Noboru, a retired Lt. General in Japan’s Ground Self-Defense Force (GSDF). The general shared his insights on the U.S.-Japan alliance and regional defense.

LTG Yamaguchi’s bio

The general graduated from Japan’s National Defense Academy in 1974 and completed the Command and General Staff Course at the GSDF Staff College in 1983. He has served in many distinguished posts, including: Senior Defense Attaché at the Japanese Embassy in the U.S. (1999-2001); Deputy Commandant of the GSDF Aviation School (2001-2002); Director at the GSDF Research & Development Command, or GRDC (2002-2005); and Vice President of the National Institute for Defense Studies (2005-2006). He retired from active duty in December 2008.

LTG Yamaguchi also served at the Prime Minister’s Office as Special Advisor to the Cabinet for Crisis Management after the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011; and was also appointed by the Foreign Ministry as a key expert in the Substantive Advancement of Nuclear Disarmament initiative. He is currently a visiting professor at the International University of Japan.

Below is a transcript of our conversation, both from the video and written correspondence (edited for space and clarity).

– – –

(Kafatos): Recently the navy of the People’s Liberation Army (PLAN) entered Japanese territorial waters and planted a buoy. Also, air incursions by PLA aircraft into Japanese airspace continue. They also launched a long-range missile into the Pacific Ocean recently. In your opinion, are these “business as usual” actions by China? Or a sign of escalating tensions?

(Yamaguchi): In my view, Chinese activity has intensified in ways different than before. 10 years ago it was more dangerous because they had fancy new ships and planes but untrained officers. Their skills as a professional fighting force had not yet fully matured.

But recent cases have been different. Chinese aircraft came very close to our territorial airspace in Kyūshū (one of Japan’s four major islands) and their flight patterns were very precise. Flying a rectangular pattern like that is doable by any professional navy. But they did it very close to our islands so, actually, I was scared and impressed at the same time. They are much more professional now, which is actually good news.

That said, violating territorial airspace is against international law. The Japanese government reacted very quickly and correctly, as is its right and duty. Now, I do not know for sure whether this recent violation was intentional. In the past Russian aircraft violated our airspace several times, mostly due to navigation errors. In the late 1980s we had to conduct “signal shots” to get them to stop doing it. Signal shots are when you fire several 20mm rounds right in front of their aircraft to get their attention.

“The U.S. might think twice about getting involved in a Taiwan contingency. But Japan doesn’t have that luxury.”

LTG Yamaguchi Noboru

As for China launching the long-range missile, that made many people nervous. But actually, that sort of thing is pretty common in international waters. This one was scary because it happened pretty close to Kyūshū. On one side of the coin, you now have a more professional Chinese military. But on the other, their actions are getting scarier to the Japanese public.

(Kafatos): With regard to a possible Taiwan contingency, Prof. Minemura Kenji at the Canon Institute disagrees with the notion that the PLA will attack Taiwan in a Normandy-style invasion. He claims the Chinese will instead take Taiwan with gray zone tactics. He says their plan hinges on keeping the U.S. military out of the fight.

(Yamaguchi): Prof. Minemura’s arguments sound very reasonable. A Normandy-style invasion would be very difficult, a hundred times more difficult than Russia’s land invasion of Ukraine, which failed and now the conflict is at a stalemate. An amphibious invasion of Taiwan would be a nightmare for the PLA. Ordinarily, you would expect mainland China to try to win Taiwanese hearts and minds over time, as we say in Japanese, to gently coax or wait “for the ripe persimmon to fall” (jukushi ga ochiru, 熟柿が落ちる). But China has kept failing to do that, and there is strong anti-mainland sentiment in Taiwan.

As for the U.S. and Japan staying out of a China-Taiwan conflict, any such conflict would involve aerial and maritime combat. I don’t know if the U.S. would automatically get involved due to the defense obligations stipulated in Article 5 of the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty. But Japan’s Yonaguni Island is only 100 kilometers (63 miles) away from Taiwan. If Taiwanese and Chinese aircraft end up battling it out 50 kilometers (31 miles) away from Yonaguni, they could be in Japanese airspace in a matter of minutes.

So, particularly for Japan, it’s impossible to avoid getting involved. If Taiwanese or Chinese military assets infringe upon our territory during conflict, even accidentally, our Maritime and Air Self-Defense Forces will have no choice but to protect our territory.

And our forces have to be ready for the very real possibility of some sort of clash. We cannot be overly optimistic that it won’t happen. The U.S. might think twice about getting involved in a Taiwan contingency. But Japan doesn’t have that luxury.

(Kafatos): Do you believe the U.S. military and Japanese SDF are taking effective actions to prevent conflict in East Asia?

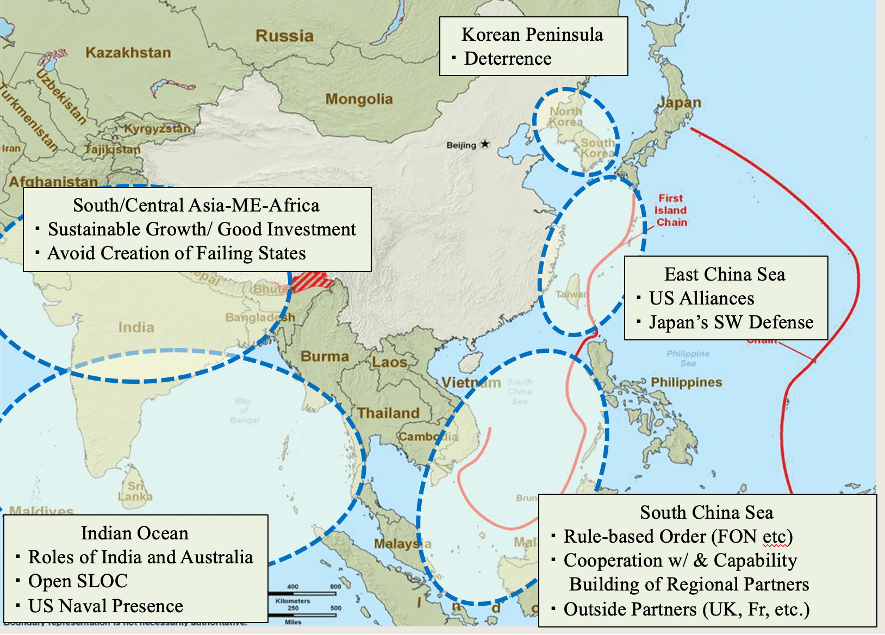

(Yamaguchi): I actually wrote about this subject in Japanese for the Sasakawa Peace Foundation. Specifically, about the U.S. Marine Corps (USMC) and their operational shift in the region, and how it relates to SDF efforts.

The SDF has done a lot to build up our defensive posture in our southwestern islands, so now we have more denial capabilities. These are completely defensive and modest capabilities, but they help us deny the area to the other side. We used to have a substantial force presence only on the main island of Okinawa. Now we have forces in Yonaguni and Ishigaki, with modest anti-aircraft and anti-ship capabilities to protect the civilian population. The SDF also has a presence in Miyako and a new station in Amami Ōshima to the north of Okinawa.

“If war were to break out with China we might not be able to win; but we are better prepared to not decisively lose either. If they attack us, it will cost them dearly.”

LTG Yamaguchi Noboru

As for the U.S. Marine Corps, they have become much more serious about defending the area. Their job is to be able to respond to contingencies anywhere in the world. During the Cold War, Marines stationed in Okinawa probably didn’t think they were there to defend Japan or Northeast Asia. But now they are shifting emphasis to what I call “expeditionary denial capabilities,” or in USMC parlance, Expeditionary Advanced Base Operations (EABO) with new types of forces such as Marine Littoral Regiments (MLR). This isn’t just infantry or artillery or armor but rather a combined force, with anti-air and anti-ship capabilities, and logistics for aviation.

That is very similar to the SDF’s defense concept, which is to strengthen denial and defensive capabilities in coastal areas. Not just in Japan, but from the First Island Chain all the way down through Taiwan to Southeast Asia and the Philippines. We are now much more able to deny access to these areas.

If war were to break out with China we might not be able to win; but we are better prepared to not decisively lose either. If they attack us, it will cost them dearly. This is what we call “deterrence by denial.” And that applies to the other side as well. They would not lose, but they could also never win. Conflict would definitely be a lose-lose situation for both sides.

(Kafatos): But the denial capability is only as effective as the will to fight. What is your opinion of the state of health of the U.S.-Japan alliance? One of the candidates running for president, former President Donald Trump, is skeptical of alliances. How would you argue against those who think the alliance doesn’t benefit Americans?

(Yamaguchi): I am not totally against that point of view. Each person is entitled to their beliefs. The Japan-U.S. alliance is based on our mutual defense treaty. But without the strong determination to implement what’s written there, what is it? It’s just a piece of paper. I drive this point home with my students all the time. Look at the Japanese-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact of 1941. The Russians violated that agreement soon thereafter in 1945.

The Japan-U.S. alliance has been intact for a long time, so that is very reassuring. Still, there are two points we need to consider here: First, alliance matters cannot be unilaterally decided upon by Japan. Alliance obligations must be related to our common interests and perceptions of common threats. If the Americans clearly didn’t care about securing U.S. interests in Northeast Asia then it would be a different story. But the Japanese and American perceptions of threats in Northeast Asia are closer than ever, so I am not overly worried.

Ultimately, it’s a matter of choice for the Americans. For Japan it’s not, it’s a matter of life or death, so we are going to be very determined. But to the extent the U.S. is determined to maintain our mutual defense, it’s not an emotional matter. It’s a pragmatic calculation that comes down to this: Does the U.S. want to lose the area? Or help Japan and maintain U.S. national interests?

Second, the credibility or reliability of the alliance has nothing to do with what is written in the treaty. And it’s not just about military-to-military relations either. What’s crucial is overall relations between the two countries. If we Japanese truly believe we need the Americans, and Americans truly believe they need us, for the future of a better world, then both sides will be serious about the alliance.

Then there is the matter of heart. When the Great East Japan Earthquake hit in 2011, I was serving in the Cabinet. And I can tell you, when Operation Tomodachi happened, nobody was questioning the credibility of the alliance. Not even the left-leaning Democratic Party of Japan.

After all, the Americans didn’t have a treaty obligation to help us with the disaster response. But they did. They sent 20 ships, more than a hundred aircraft, and thousands of marines, sailors, airmen, and soldiers. From our point of view, there is no doubt. When Japan is in a difficult position, our U.S. friends will help us.

The strength of the alliance depends on the overall relationship between the two nations. And if we appear united, this may deter opponents from doing anything against either Japan or the United States. But maintaining the alliance requires continuous effort from both sides. And we have to keep working at it, even if we think the state of the alliance is good.

(Kafatos): Mr. Ishiba Shigeru recently was elected prime minister. What kind of changes do you think we will see in Japanese defense policy? Or what will be the difference between the Ishiba and Kishida administrations?

(Yamaguchi): When talking about Kishida’s policies, you have to consider Abe. Kishida executed defense plans laid out by Abe, which were very ambitious (such as the increase in defense spending up to 2% of GDP). That would not have been possible under Abe Shinzō or Asō Tarō because of their hawkish reputations. But Kishida represents the liberal constituency of Hiroshima, which is strongly against nuclear weapons. He was able to implement these policies because of his liberal reputation. Just as Nixon was arguably able to make a deal with the Chinese in 1972 because of his right-leaning policies. The U.S. public may not have allowed a left-leaning president to do that.

Turning now to Ishiba and Abe, the Peace and Security Law was passed in 2015. Ishiba wanted to first change the fundamental laws pertaining to national security and then position an SDF law under that. But the Abe administration took a more pragmatic approach, which was to put the fundamental idea in one law and change interpretation of existing laws. Ishiba disagreed and wanted much more fundamental change.

I knew both Ishiba and Abe when they were young politicians. Both were known as security experts in their conservative party, the LDP. Perhaps Abe was the more pragmatic of the two. I am concerned that if Prime Minister Ishiba thinks something is wrong, he will want to change everything. Start again from scratch. He feels strongly about the need for these changes but they are probably not a big priority right now. I don’t think he will do it but it is a concern, so we’ll have to see.

I would rather see him focus on the economy and recovery efforts after recent disasters, something he has been vocal about. Without recovery Japan will not be united.

(Kafatos): As you know, in the U.S. Vice President Kamala Harris is running against former President Donald Trump. Do you think Prime Minister Ishiba will have good relations regardless of who wins? And from the standpoint of Japan’s defense and foreign policy, which of the two candidates would be better for Japan?

(Yamaguchi): It’s a really good question. We have two big elections coming up: the Oct. 27 snap election (called by Prime Minister Ishiba) and the U.S. presidential election. Both are decisive and I don’t know how they will turn out. The presidential election alone scares me. Neither candidate seems terribly interested in bridging the divide between Americans, and Trump is unpredictable. Regardless, our nations need to strive for an even better relationship.

You know, I’ve never failed in predicting what will happen in international relations because I never try to predict (laughs). Responding to change has always been part of my job description, when I served in government and even after I retired. But I don’t think it’s a good idea to worry overly about what-if scenarios. That’s probably not helpful. Sure, thinking about different scenarios can help us find ways to deal with unknowns. But honestly, I have no idea how things will turn out. What I do know is the mission for Japan is very simple: keep the alliance intact, and maintain good relations with the United States.

(Re: hosting nuclear weapons on Japanese soil)

LTG Yamaguchi Noboru

“Ishiba and Abe helped move those difficult discussions forward. But I feel like we still have a long, long way to go.”

Looking back at Abe, his administration had the full support of career public servants in the various ministries. He used to listen to stakeholders from the ministries of finance, defense, foreign relations, etc. But Prime Minister Ishiba does not have that kind of experience. When he was defense minister he exhibited very good leadership, but he had his own ideas about defense. He would see me in my green (GSDF) uniform and say half-jokingly, “Your army has too many soldiers.” He thought the other branches should be given more money rather than spending money on soldiers. That was his way of thinking, which I didn’t agree with.

(Kafatos): Did Ishiba think it was necessary to increase the strength of the maritime force or air defense force? What did he mean by “too many soldiers”?

(Yamaguchi): Back then we had very strict limitations on the defense budget. But Kishida doubled the budget, so now you won’t see as much fighting between the services for money. In that sense, we are in a much better position than before.

Now it’s about building seamless connections between the different services. Everybody in the Ministry of Defense is talking about cross-domain and multi-domain concepts, including cyber, space, and electromagnetic domains. That will require a merging of services, where, regardless of which service “owns” a particular asset – regardless of who the shooters are or who owns the sensors or transmitters – that asset needs to be usable by everybody. That is the essence of cross-domain operations, and I expect rivalries between services will not be as bad as before. By the way, my son is a submariner. And we have never agreed on things (laughs).

(Kafatos): Ishiba wants to acquire nuclear submarines. He has also talked about nuclear sharing where U.S. nuclear weapons would be deployed on Japanese soil, and establishing an SDF base on U.S. soil. What do you think? Are his defense policies more hawkish than the late Prime Minister Abe’s?

(Yamaguchi): Well, let me first comment on nuclear-powered assets. Because of our unfortunate history – not just Hiroshima and Nagasaki but other events as well where Japanese were exposed to radiation, such as at the Bikini Atoll – these experiences deeply affected the Japanese mindset about nuclear technology. In the past there were attempts to field nuclear-powered merchant marine vessels, but those failed due to radiation leaks. And our nuclear power plants as well; they were shut down after the Fukushima disaster on 3/11 and ever since we have struggled to restart them. This is an issue deep in the psyche of the Japanese people. It’s not something that can be considered strictly from a logical standpoint.

As for nuclear sharing, my question is this: will Japanese operating such assets have the resolve needed to use them? To share the trigger and the responsibility to shoot nuclear weapons? I can tell you, if I were tasked with that duty I would have the resolve to do it. And I am sure Prime Minister Ishiba would, too.

But I don’t know what percentage of the Japanese public would have that kind of resolve. Do they truly understand the reality of the situation? It’s shoot or be shot. That is why such weapons exist, to use if deterrence fails. Ishiba and Abe helped move those difficult discussions forward. But I feel like we still have a long, long way to go.

(Kafatos): At the 2+2 this past summer, the ministers discussed the Japan Joint Operations Command (JJOC) initiative to build a more robust command structure between the U.S. and Japanese militaries.

(Yamaguchi): The tighter and more connected we are, the more it increases our bilateral capabilities. The command structure is the organization’s brain and nervous system. Those nerves connect to the eyes, ears, and to the fist. That’s what helps us use our hardware better. These structures exist in the U.S. and Japanese militaries, and Japan has been working hard to improve its joint capabilities. JJOC is a good chance for the two militaries to connect and intermesh on multiple levels rather than just one or two.

(Kafatos): There’s the so-called “Five Eyes” intelligence-sharing initiative. Is Japan ready to be the sixth eye?

(Yamaguchi): I don’t know. It has always been a dream of Japan’s intelligence and military establishments to share intel with the Five members. These nations have, after all, the best five of the world’s top ten intelligence agencies. The question is, is Japan ready for that? Particularly in terms of information security. We have made progress in policies and security systems, but I don’t know how far we have to go to be at the same level.

Another issue is, in their view, will it be worth sharing with Japan? And what about Japan’s role in security and intelligence? Will what we have to offer be important to them? The Five are a lot more serious than ever about the importance Asia, in terms of their own strategic interests. But will that be enough to make them want to share fully with Japan? These are some of the questions I have.

(Kafatos): As we transition to 2025, as a person interested in the defense of Japan, what will you be looking for in terms of the defense situation in the region?

(Yamaguchi): There is a lot of uncertainty surrounding the two upcoming elections. There is some worry there. The Ishiba administration has been working really hard the past couple weeks. But the bottom line is, how strong will the new Ishiba administration be domestically? That will depend on how well he does in the upcoming election.

I am an optimist by training because I had to fly single-engine helicopters and never once experienced engine failure. But, given the situation, I have a couple good reasons to be concerned about the less optimistic scenarios. If our executive branch is not strong and united then Japan’s resolve as a nation will suffer.

As for the U.S. election, to what extent will the winning candidate be able to unite the American people? That will be key. Not only for bilateral or domestic issues but for the world as a whole. That’s the degree of magnitude. That’s what’s at stake here.

Regardless of how it turns out, at the policymaking and working group levels, it is clear the Japan-U.S. relationship is better than ever.

So, at least that’s very good news.

– – –

In addition to the achievements listed in his bio, Lt. General Yamaguchi holds a Master’s degree from the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University. He was also a National Security Fellow at the John M. Olin Institute for Strategic Studies at Harvard University from 1991-1992. His recent publications include “Japan-India Security Cooperation: In Pursuit of a Sound and Pragmatic Partnership” in Poised for Partnership: Deepening India-Japan Relations in the Asian Century published by Oxford University Press. The Japan Lens thanks him for his time and insights.

Photo 1: LTG Yamaguchi Noboru at his retirement ceremony from the GSDF in Camp Asaka (Nov. 2008).

Photo 2: LTG Yamaguchi speaking at an event at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in Washington, D.C. (summer 2014).

Photo 3: DOD map from LTG Yamaguchi’s article for the Sasakawa Peace Foundation titled The Geostrategy of BRI vs. FOIP and the Role for Japan published in 2021 (link). The author made notes here regarding China’s A2AD.

Photo 4: LTG Yamaguchi at the National Defense Academy with U.S. Lt. Gen. Gregson and VADM Ohta (July 2012).

Photo 5: LTG Yamaguchi in the cockpit of an AH-S1 helicopter prior to takeoff from Camp Tachikawa (fall 2008).

No machine translation or artificial intelligence programs were used in the creation of this post.