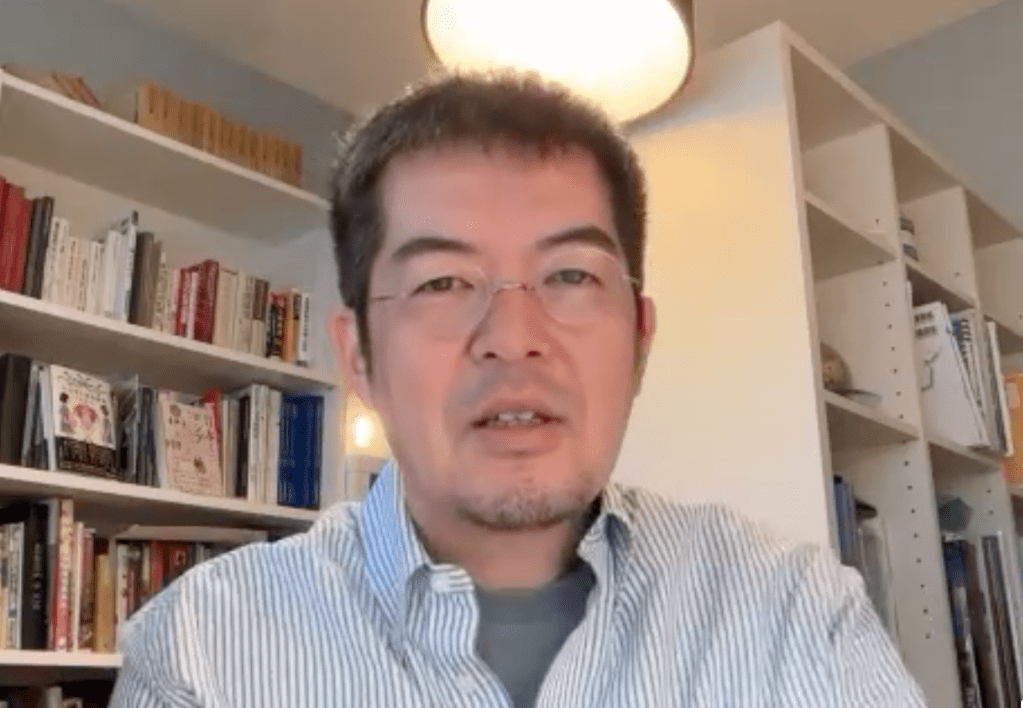

A story published last month in the Asahi Shimbun featured Konishi Kazuyoshi, a high-profile political journalist in Japan. During his career he covered front-page news stories across the globe. But this article on Konishi was not about a hot story he grabbed onto. Rather, it was about what he let go of, and what he gained in its place.

Konishi, who hails from Saitama Prefecture, studied business at Japan’s prestigious Keio University and government policy at Hōsei University. In 1996 he joined one of Japan’s largest news agencies, Kyodo News, and went on to become a top political journalist.

Despite changes in Japanese society, journalism is still very much a man’s world, and nothing is more masculine than working the corridors of power in Nagata-chō. It’s like being a hotshot reporter assigned to the White House. In fact, he covered stories there, too.

In 2017 Konishi, a married man with two kids, was approached by his wife with a startling announcement: “My company is sending me to the United States.” She had to go so, if he intended to stay in Tokyo, she would have to take their kids who were five and three at the time.

Konishi knew it wouldn’t be feasible for her to work full-time and take care of the kids. After agonizing over what would happen to his career, he filed for a special three-year leave of absence for trailing spouses. Just this act alone was unheard of for most Japanese men. Even women, hesitant to take leave for the trouble it will cause co-workers, often choose to quit instead. But Konishi, a positive-minded person, believed he would be able to come back and pick up his career again. He decided to take the plunge.

Female co-workers and junior reporters gave him words of encouragement. “It’s really cool what you’re doing,” they said. But colleagues of the old guard, raised with the work-trumps-everything mindset of the 1980s, were not so encouraging. “Konishi is doing what?? Following his wife overseas? His career is over.”

“Japan’s culture has been male-dominated for so long.

Konishi Kazuyoshi

Unless that changes, there is no future for Japan.”

With much trepidation, he moved with his family to New Jersey in 2017. We recently interviewed Konishi to hear the rest of his story in his own words. (Spoken and written content have been edited for flow and clarity.)

– – –

(Kafatos): So what happened after you arrived in the U.S.?

(Konishi): At first there was a lot to do. I was busy unpacking and getting our new home settled. I was sending my wife off to work and the kids to school. And then, after things settled down, the reality set in. In a blink I had gone from being the biggest earner to being dependent on my wife’s income. My title went from “political reporter, Kyodo News” to being just “papa” to my kids.

I started to really worry about what would happen to my career. I wasn’t taking a few months off. It was a few years! Being gone that long from the political beat, would I even be able to keep up after being out of the game that long? And who was I now, anyway? I suffered an identity crisis.

(Kafatos): How were you able to overcome that?

To be honest, it took me a while to figure out who I was, to accept myself as I was. I went through a lot of ups and downs. Then a friend in Japan asked me to write a column for Fukui Shimbun on my experiences as an expat. I jumped at the opportunity.

This time I wasn’t writing a political news column. It was about my life in the U.S. as a stay-at-home dad, and it started gaining readership. That became the answer for me, and I was able to use some of the skills from my previous life as a journalist. I also met other Japanese men in the area who were in the same boat, men who could understand the things I was struggling with. Just knowing I wasn’t alone was hugely encouraging.

(Kafatos): Is that how you started your support group?

(Konishi): Yes, I launched a group in 2018 called “Friends of Expat Husbands and Husbands Around the World”(世界に広がる駐夫・主夫友の会). I knew that as more women in Japan entered the workplace and norms continued to change, there would be more and more men like me. What started as four of us has now grown to about 170 members.

(Kafatos): Speaking of norms, working overtime (zangyō) has always been expected of Japanese workers. This is cited as one of the reasons it’s hard for Japanese couples to have kids. What are your thoughts on that?

(Konishi): The data is clear: Japanese work too much. The situation is better than before but it’s still a big problem. And this overtime burden falls disproportionately on men, even in a dual-income situation. As a result, women have to do more of the housework. The average Japanese man does 41 minutes of house-related chores per day. Women do five to six times that amount. And for every hour of paid work a woman completes at her workplace, the average man works almost double that. These are some of the worst rates of imbalance in the world.

What’s the result of all this? The obligation to work falls disproportionally on men. Men suffer higher rates of premature karōshi deaths– literally being worked to death.

“Gender inequality in Japan must be eliminated as soon as possible. And I am convinced the root of all evil lies in long working hours.”

Konishi Kazuyoshi

Also, this contributes to keeping women from rising in the workplace. If their husbands work lots of overtime – and this has been a requisite to getting promotions – then wives can’t put in as many hours at their workplaces because they have to do all the housework their husbands can’t or won’t do. Such women are less likely to get promoted. Their career prospects are literally hobbled by how much their husbands work.

Gender inequality in Japan must be eliminated as soon as possible. And I am convinced the root of all evil lies in long working hours.

(Kafatos): In your honest opinion, do you think it would be a good thing if more Japanese men followed your example? How would you respond to those who say an important part of Japanese culture will be lost?

Japan is not projected to achieve much more economic growth. The workforce is dwindling. In order to tap into this underutilized workforce of women, men must change their attitudes and actions. If men change, women can change. Japan’s culture has been male-dominated for so long. Unless that changes, there is no future for Japan.

(Kafatos): What’s your response to conservative commentators who say Japan’s declining birthrate is due to women entering the workforce and abandoning the home?

(Konishi): The declining birth rate is due to a number of factors. But in the context of this conversation, if a working mother has a husband who can’t or won’t help out at home, a huge burden falls on her with each child they have. The financial costs are also enormous. That’s why many of today’s women are saying one child is enough, or choosing not to have any at all. Or to not marry at all.

I think we need a diverse range of people working in Japanese politics. Things have been run by elderly men for too long. They’re old-fashioned and kind of macho in a way, so they think men should work and women should stay in the home. But going back to that old family paradigm of the 1970s and 80s is totally unrealistic in today’s world.

And if the government doesn’t create effective policies to address it, Japan’s declining birthrate will only worsen. The only way to change this highly homogeneous “gotta work hard” macho culture is to get women and young people to participate in politics.

(Kafatos): The Japanese government is calling on companies to reduce overtime but they themselves work many hours of overtime. They don’t seem to be leading by example.

(Konishi): This is a huge problem. People are quitting the public sector and fewer are applying for those jobs. Many ministries and government offices have this macho work culture, where people are just expected to toughen up and work hours and hours of overtime.

Government officials in Kasumigaseki are forced to work late into the night to produce parliamentary answers for politicians. The situation has improved a little, but they still work an unusual amount of overtime. The same is true in Nagata-chō, Tokyo’s center of power where the Prime Minister’s offices are. The toxic work culture expects both men and women to be strong, to tough it out. By making strength the central axis of both men and women, this macho culture continues.

The downside to this do-or-die culture is that it leads to a strong sense of homogeneity. When homogeneity is strong, everyone tends to think and act in the same way. Policymakers steeped in this work culture become less open to new ideas.

“What hasn’t changed? Men’s perceptions. Many still believe earning is what makes a man manly.”

Konishi Kazuyoshi

Another issue is men tend to go out drinking after work. They’d rather do that after a long day than go home and do housework or help with the kids. And this is part of a bigger problem: men don’t really want to deprioritize their careers. Japan’s paternity leave is one of the most generous in the world. But taking a year off to help out at home is unthinkable to most men. There’s this stigma, this fear of being asked at a job interview, “Well, what were you doing during this gap in your resume?” We Japanese men need to rethink our priorities in life.

(Kafatos): Is that because the image of masculinity has always been work, and nothing has been created to replace that ideal?

(Konishi): Well, not everyone is in a position to do what I did. My wife was sent abroad and her income supported us, so I was able to leave work for a few years. But quite a few men who take a break from their careers are able to find work again. I think stepping away from the rat race is useful in reevaluating. You can travel, go back to school, and ultimately lead a happier life.

The idea that husbands must work hard and earn for their households is deeply rooted. But wives are increasingly less impressed by this kind of work martyrdom, especially when they’re working too. Despite that, men go out of their way to shoulder this extra burden. And perhaps that’s why the rate of suicide in Japan is so high. When things don’t go well at work, it’s a huge blow to a man’s ego. To his sense of self.

(Kafatos): Perhaps a new model of masculinity is needed. In that sense, men like you are pioneers.

(Konishi): That old paradigm of men working and women staying at home might have worked well during the high-growth years (1950s-80s) or even after (1990s-00s). But women are entering the workforce in huge numbers. Lots of things are changing.

But what hasn’t changed? Men’s perceptions. Many still believe earning is what makes a man manly. And, frankly, it stresses them and the whole family out. It wears them out physically. In my talks my message is, “It’s time to put an end to this outdated thinking.”

Men have to change, first our actions then our values. If we’re able to do that and live a more balanced life, it’s good for the whole family.

(Kafatos): Tell us about your recently published book titled The Dilemma of Husbands Whose Wives Earn More Than Them (妻に稼がれる夫のジレンマ). What kinds of reactions are you hearing from male readers?

(Konishi): I wrote that book based on my Master’s thesis, which I wrote after interviewing twelve men who were trailing spouses. Some readers said it was too vivid. I wrote about fights couples were having, such as a woman shouting at her trailing husband, “Who do you think pays for all this?!” That was hard for some men to read. But I think my book is relevant to men all over the world, especially those in countries that have cultures like Japan’s. Like South Korea. The male mentality there is very similar to what we have here in Japan.

(Kafatos): Perhaps that’s one reason we’re seeing more populism throughout the world. Maybe it’s a backlash against these changing gender norms. Are you optimistic about your chances of success?

(Konishi): First, about populism, I think you’re right. We’re seeing it in America and throughout Europe. Clinging to old norms isn’t just a Japanese problem, but it’s so profoundly pronounced here. It hinders women’s opportunities and saps the strength of the nation. Men and women need to respect each other with equality. That’s the way forward.

As for our chances of success, the road is long and steep. I think I have a unique role to play in getting the word out. To say, “Hey, there’s another way of doing things, I’m living proof of that.” But each and every man needs to change his own perceptions. And Rome wasn’t built in a day.

Japanese women have been talking about the gender gap for years, to no avail. It hasn’t resonated with men. The mindset has been, “Gender equality? That stuff has nothing to do with me.” Frankly, that’s how I was back when I was a political reporter.

But that experience in America changed me. And I’m betting when the message comes from a man who used to think like they do, men will be more receptive. My book features other men who’ve taken a different path as well, so it’s not like I’m some special case or something.

We can do it. We can all do it.

– – –

Konishi Kazuyoshi was a visiting fellow at Columbia University, and was also a participant on the U.S. Department of State’s International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP), which has many leaders and heads of state as alumni. He continues to write and give talks on behalf of Expat Friends of Husbands. Konishi’s official website and blog are available in Japanese. The Japan Lens thanks him for his time and insights.

Photo 1: Profile photo of Konishi Kazuyoshi (Nov. 2023).

Photo 2: Konishi in his former life covering a story at the White House (April 2012).

Photo 3: Konishi on the press corps accompanying the prime minister (April 2012).

Photo 4: Konishi giving a lecture on gender issues (Jan. 2024).

No machine translation or artificial intelligence programs were used in the creation of this blog.

3 responses to ““We Japanese men need to rethink our priorities”: Konishi Kazuyoshi on gender inequality”

[…] chu-otto (駐夫) – for trailing husbands overseas such as himself. In 2024 The Japan Lens interviewed him about this experience. He is now the representative of Expat Friends of Husbands, which boasts 210 […]

LikeLike

[…] move now makes him look modern and ahead of his time. This is important given how many Japanese are rethinking their traditional work values and seeking alternative role […]

LikeLike

[…] タイトルは、『Konishi Kazuyoshi on Gender Inequality: “We Japanese men need to rethink our priorities”』 (日本の男性たちは、自らの優位性を捉え直す必要がある) […]

LikeLike